All That Jazz: Menswear and accessories from the 1920s

[portfolio_slideshow include=”1601″]

BY KELLY SKINNER

We’ve long been in the throes of ’20s fashion—the splendor, the romanticism and the transformative changes in womenswear still have us transfixed. But, with the release of Baz Lurhmann’s The Great Gatsby and the continued popularity of Downton Abbey, we’re forced to ask another pressing question.

- Knot cuff links in 18 karat gold. Photo courtesy Tiffany & Co.

“What about the men?”

See the influence of 1920s styling in Louis Vuitton’s latest menswear collection.

“If one had money, the stratification was pretty clearly defined,” says Mark-Evan Blackman, assistant professor of menswear at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “Men wore morning coats, waistcoats and striped trousers. Someone educated was not seen outside during the day without those clothes. Even sportswear was formal.”

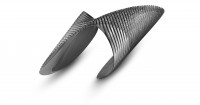

And, one should note, life was all about sports—sailing, tennis and horse races ruled. Which is how two-tone wingtip or “spectator shoes” came into fashion. According to the tome, Fashion, Costume and Culture: Clothes, Headwear, Body Decoration and Footwear Through the Ages by Sara and Tom Pendergast, these shoes were “part of fashionable men’s wardrobes during the Roaring Twenties,” and the cut “soon became one of the most popular conservative shoe styles for men.”

Hats continued to dominate men’s dress, with the fedora rising in popularity in the ’20s thanks to Prince Edward VIII (who had started wearing one with his dress suits). According to the Pendergasts, these wide-brim incarnations were “mass produced by Sears Roebuck” after the prince visited the U.S. in 1924, “and soon, most well-dressed American men wore a fedora.” If not a fedora, it was typical to see businessmen and bankers donning bowler or derby hats; which stayed in fashion through the following decade.

- Burberry London Poly-Cotton Trenchcoat, Black, at Neiman Marcus, neimanmarcus.com.

When it came to clothing, though, men stuck to the classics, and in a restricted color scheme of natural hues like browns, greens, blacks and grays. “You saw multiple pleats, waist-suppressed garments, suspenders connected to the jackets, and you saw a change in cuts—men’s waists were higher, their arm holes were higher and the waist bands ended at one’s navel,” adds Blackmon. The ’20s also heralded the trench coat, which was developed by Tom Burberry for WWI soldiers, an echo of the coat as we know it today.

The war also affected the way men told time. “If you were driving a tank, you couldn’t look at your pocket watch,” says Michael Coan, chair of jewelry design at Fashion Institute of Technology. “So, Cartier developed the Tank watch, which resembled the tire tracks of a tank.” Rolex and Hamilton were also major watch manufacturers of the period, and started accenting the wrists of the middle-to-upper class with their ornate timepieces. (Coan anticipates a return to hand-crafted watches like these). Cuffs had also changed in cut, and brought with them showier cufflinks. “In the ’20s, fantasy came out. They were trying new colors, sapphires, mother of pearl, and diamonds,” says Coan of the stones that accented formal cufflinks.

Glamour spilled over into the daily covetables, too. Men wore ID bracelets (also inspired by the war) by Reed & Barton or Tiffany & Co., donned whimsical pins by Raymond Yard, carried an Art Deco cigarette case by Alfred Dunhill, and likely an intricate fountain pen and sleek card case. Influenced by the women, the culture, and icons like Cole Porter, Charles Lindbergh and Rudolph Valentino, the overall look for men was polished and smooth, with a little bit of flash.

Gunning for Gatsby? Us too. And now, more than ever.

-March 2013