Art, science, magic: The life of a designer

Jewelry creator finds inspiration in little-known places

BY MICHELLE VALENZUELA

The branch of a tree.

A waterfall.

An astronaut landing on the moon.

Mary Ann Scherr sees inspiration in everything.

One peek at her body of work and the diversity of influences is clear. You see sculpture, necklaces, rings, bracelets. You see silver, gold, aluminum, titanium, porcelain. You see delicate curves, solid pyramids, hidden messages.

“A showcase of my pieces looks like 20 different people,” Scherr said.

Listen to the stories of her adventurous life, and you see how that variety of interests plays out in the twists and turns she’s taken in her 90 years.

Bob Hope, cookie jars, and titanium

Scherr is a jewelry artist whose works have been displayed in museums and galleries all over the world. Her pieces reside in permanent collections at the American Craft Museum, the Smithsonian museums, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among others. She has taught at institutions including Kent State University, the Parsons School of Design, and Duke University, and she currently teaches at North Carolina State University.

The Ohio native estimates she has designed more than 10,000 pieces on commission for clients, among whom are the Duke of Windsor, Liz Claiborne, and Chelsea Clinton.

Her life is filled with so many remarkable stories that she has written a 300-page book for her three children.

Some of the more eyebrow-raising highlights:

- At 22, Scherr canceled a movie contract with Bob Hope when she realized she wanted to pursue art instead.

- Scherr designed a line of cookie jars commissioned through her husband’s design company. She wasn’t proud of the jars; in fact, she hid her samples in a closet. Twenty years later, they surfaced in Andy Warhol’s collection. “The Cow Jumped Over The Moon” was auctioned for $19,000. “I still kind of hate it though,” she said.

- For an exhibit in the early 1980s, Scherr created a line of jewelry using a new technique that colors titanium.

Scherr laughs at any hint of awe at her accomplishments. “I’m a restless soul,” she said.

Passion and drive have led to her most beloved project, one that stretched her imagination and skills and landed her in major newspapers and on television shows such as “Today,” “Good Morning America” and “The Johnny Carson Show.”

Doing the impossible

It started with a commission that she wasn’t excited about. In the 1960s, the mayor of Akron, Ohio, asked Scherr to design a gown for Ohio’s Miss Universe contestant. Because the first astronauts in space were from Ohio, the theme for the outfit was the galaxy.

As Scherr worked on an aluminum belt for the outfit, she watched, awestruck, as Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. On television, she saw graphs of the astronauts’ heart activity as it was monitored by NASA. She created the belt to simulate the astronaut body monitors. It soon occurred to her that this monitoring could be done on Earth. She set out to design working medical pieces that were masked as jewelry. Patients could wear something beautiful instead of unsightly equipment.

Her first project was a piece that would measure air quality and alert the wearer to unhealthy fumes. No one thought such a thing was possible. This was 1969. Air quality devices took up an entire wall. They couldn’t be worn on a human body.

Then Scherr met an electrical engineer she calls “one of the unusual persons who had an imagination.” After about a month, he had reduced the size of the mechanical part to a few inches. The completed jewelry piece, made of silver and gold, is box-shaped with metal fringe dangling from the bottom. When bad air is detected, the song “Smoke Gets In Your Eye” plays.

Scherr designed many more body monitors and got patents on some of the creations. The dearest piece to her heart is her portable EKG machine. It took about a year to complete and employed a liquid crystal technique Scherr had used in other work to measure temperature and color. Scherr collaborated with a research bioengineer to create the prototype. On testing day, they put the piece on a model and nervously turned it on. They jumped and clapped and danced when it worked. Scherr said it was one of the most important things she has ever done. She likened the experience to having a baby. “I felt that way when we plugged her in. It was quite a moment.”

Scherr continued to develop body monitors, and what started as a jewelry project became a scientific one. Jimmy Carter allocated $14 million to the University of Akron to develop the products. Scherr was the design consultant. After the Iran hostage crisis, the program was one of many that were cut.

But Scherr didn’t give up on the idea. She continues to work on the body monitor project. In 2011, Scherr, along with Dr. Troy Nagle of the biomechanical division of North Carolina State University, developed a monitor that works by remote.

‘I learn every day’

Mary Ann Scherr never stops and never gives up. Her goal is to produce a piece of jewelry every day before she goes to bed. She supplies items for galleries in Boston and in the North Carolina cities of Asheville, Penman, Raleigh and Durham.

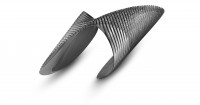

The Smithsonian recently put one of Scherr’s necklaces on a T-shirt for sale in its museum shops. The necklace, called “Waterfall,” is in the permanent collection at the Renwick Gallery. The stunning piece drips with layers of long silver streams that mimic the fluid movement of water.

Scherr made most of the components for the necklace in the car. She and her husband were on a road trip, and there’s nothing Scherr hates more than being idle. “I get bored sitting there,” she said.

Scherr has to have an outlet. She has to have work to do, and she likes the work to be different every time. The only items that she repeats are her “message rings.” The rings, typically made of gold or silver, contain images that relate to the lives of the people who commission them.

Scherr doesn’t tire of making the message rings because no two are alike. And Scherr never tires of the creative process, of teaching, of learning. She says curiosity is the key to having an interesting life.

Scherr turns 91 in August. She is fascinated by the history of metal techniques and is exploring old and new ways of making interesting artworks.

“I learn every day,” she said. “There’s no end to what you can learn.”

-September 2012